The Silly Magic of Asian Martial Arts versus Reality

The Silly Magic of Asian Martial Arts

versus Reality

Mike Sigman: March 2020

I was reading some remarks by a "Tai Chi"

enthusiast and I spotted right away that there was something not right with his

mentation … his words were full of nonsense prattle and attempted to portray

some knowledge of Hidden Secrets that he was privy to. The more I thought about it, the more I

thought "this guy is really doing nothing different than a lot of

established "Tai Chi Teachers".

I've watched a couple of qigong videos in the last week or

so and I decided it was a waste of time for people to take these online videos

seriously. I watched one video by an

absolute master/expert that I know personally, and the video was very clear in

how the choreography went … however, I knew that this man would never discuss

or explain the ramifications of the breathing, qi, jin, and involvement of the

subconscious mind. So basically, most

people would simply learn a choreography that looked nice, was exotic, and

perhaps would have a placebo effect on their health.

The other video I watched was put on proudly by a middle-grade

"Tai Chi Teacher" who was proud of his qigong and took great pains to

explain the choreography, distances between fingers, and so on. This man I took to be the downstream

descendent of someone further up the line that never explained all that was

involved in a qigong. Why not? Most of the people who do and teach

"Taiji" in the West are the downstream results of limited upstream

information.

So I began thinking of how I would describe the problem that

I think we have.

The main problem is that the traditional Chinese view of

movement is not the one we in the West have concluded as our basis for

physiology and kinesiology. Despite the

attempts to simulate Chinese martial arts, most westerners are moving, etc., within

the realm of western physiology that would be accepted at, say, any normal

health club in the US or UK, and so on.

We tend to interpret words like "center" as meaning "core

muscles", "grounded" has to do with "relaxed and stable",

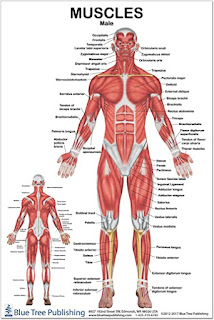

and so on. Anatomy charts show muscles,

bones, and organs. Think of a typical musculoskeletal

anatomy diagram.

That's not the way the Chinese traditional view works. The traditional Chinese view of body-mechanics

includes the fact that our normal movement is aided by many subconscious/unconscious

additions to our normal movement. We may

voluntarily hold an object like a bag of groceries, for example, but our

subconscious mind is calculating and allowing for the addition of weight to our

structure and is making micro-adjustments to our frame accordingly. The many small involuntary muscles attached

to fascia and frame and subject to our subconscious mind are therefore a

constant contributor to our movements.

The ancient Chinese analyzed and systematized this important aspect of

all movement and added it their perspective of how the body moves and works. Think

of the Chinese view of movement as the western view of movement, but with the overlays

of the involuntary-muscle systems throughout the body and the subconscious mind

as the controller that we don't access except through imagery, imagination, and

so on.

The "magic" and qi-talk in the West about Chinese

martial arts come in because most westerners don't have a grasp of these added factors

of movement … so they use qi-babble, spiritual-babble, and techno-babble to

cover the fact that they don't really understand how it all works. That, or they assume that there is no difference

between the western view of movement in martial arts and the Chinese view of movement

in martial arts.

The

Chinese View of our normal muscle-bone-tendon Body Mechanics

Movement

forces 'flow' along the Muscle-Tendon Channels

From the ancient Chinese perspective there must have

appeared to be a system of muscle/bone/tendon force flows in the body and a

system of supplemental strengths and involuntary actions that supported the

normal or voluntary motions. As an

example of an ordinary path of forces, consider holding a glass of water out in

front of you with one hand. A. There will be a path of

stresses that come along the top of the arm and up onto the neck and head, as

part of the forces that hold up the arm; the head is ultimately stabilized by

the body structure that goes to the ground. B. There will also be a

palpable path of stressors along the top of the arm, over the trapezius muscle,

down the back, across the buttocks and down the back of the leg(s) to the foot,

and thence to the stability of the ground.

This pathway is an example of the "Yang" muscle-tendon

channels that are used for Opening the body, i.e., making the back/outsides

of the body function as extensions.

Generally speaking, you can think of the Yang channels as carrying the solidity of the ground up the back/outsides of the body to the hands; the Mingmen area (which is just the backside of the dantian area) is the mediator/control region for those Yang/Opening forces.

Generally speaking, you can think of the Yang channels as carrying the solidity of the ground up the back/outsides of the body to the hands; the Mingmen area (which is just the backside of the dantian area) is the mediator/control region for those Yang/Opening forces.

All in all, there are twelve muscle-tendon channels that either Open (extensor) or Close (flexor) the body, in various combinations of usage. Most Opening channels are along the back of the body and the outer surfaces of the limbs. Most Closing channels are along the front of the body and the inner/undersides of the limbs, contracting toward the middle/dantian. For all practical and general purposes the body can be thought of as an Open and Close mechanism, constantly going from one extreme to the other in sophisticated traditional movement: the cycle from Open to Close is called Taiji (Tai Chi). Animals all tend to use the Open-Close cycle … an obvious example can be seen in this illustration of a running cheetah, but it's pretty much the same in all four-legged animals and we're just an outgrowth of a four-legged animal:

The traditional

Chinese consideration of involuntary-muscle/subconscious assist to movement

Imagine being back in the ancient days and you could feel

subtle shifts of involuntary-muscle stressors and strengths in your body when

you imagined various forces and movements from different directions … if you

didn't know about involuntary-muscle systems, mightn't you posit some artifact

named "qi", with an attendant meta-theory, to explain that tangible

feeling inside that accompanied movements or imaginings of movement? All of the skills attributable to qi,

including the exotic ones involving feelings, can be described by the actions

of the subconscious mind on the involuntary-muscle systems of the body.

The question for most westerners is whether they will

adhere to the qi-paradigm as a fetching enticement to fellow enthusiasts, or

whether they will accept various "qi" phenomena as the use of innate

body skills as an adjunct to our movements.

If the muscle-tendon channels are the connected

muscle-tendon paths of forces, at a given moment, the superficial involuntary

muscle-systems, if they are to assist the muscle-tendon channels, must adhere

to the same routes taken by the muscle-tendons: so the paths of the superficial

involuntary-muscle systems will overlay the muscle-tendon channels and will

also draw their forces from the solidity of the ground and/or the down-pull of body-weight,

as do the muscle-tendon channels. Not

all of the involuntary-muscle systems are related to the musculoskeletal system,

it should be mentioned. For example, the

vascular/circulatory system of the body can be manipulated, to varying degrees,

by engagement with the subconscious mind via imagery: vaso-dilation and

vaso-contraction as effected by imagination has been proven to work in

biofeedback studies for many years. The

Chinese and other Asians think of temperature manipulation by vaso-manipulation

to be a valid example of the body's qi.

As an aside, it should be noted that cultivating a rapport with

the subconscious mind is a foundational element of practices involving the

qi-paradigm. Since the subconscious is

the main controller of the body, with access to all of its parts, information

inputs, and so on, the general idea is to spend amounts of time in meditation

and other practices in order to form a good rapport. It is fairly common, as part of the rapport

practices, to do qigongs which allow for "possession" of the body by

the subconscious mind. But that's

another topic for another time.

Back to the choice between "magic" and the

realities of body mechanics

Without getting too deeply into the weeds of the many facets

of the qi-paradigm v. western-physics paradigm, let's get to the point about dubious

qigongs and the dubiousness of choreography and technique-focused 'forms'.

Qigongs are literally qi-tissue exercises, meaning that

you're working to improve and strengthen those involuntary-muscle systems. A lot of the involuntary-muscle cum fascia

cum subconscious systems are actually dual-purpose systems, in that you can control

an area or function voluntarily in some respects and involuntarily in other

respects. As an example (there are many)

our breathing is normally involuntary, but we can stop and start and otherwise

control it voluntarily … to a limited degree (you can't, for instance, just

stop your breath and kill yourself). Another

example would be waste elimination: you have some aspects of voluntary muscular

control, but the subconscious keeps you from wetting the bed. Another example might what is called

"abdominal guarding" where, for example, the subconscious mind will

trigger a held contraction of the muscles above an infected appendix in order

to prevent injury; normally you can contract or release those muscles

voluntarily. This last skill reminds me of

the fact that some of the qigongs that protect martial-artists from blows,

etc., are purportedly the result of a monk named Hung Hui discovering that control

of the involuntary-muscle systems could provide an "iron shirt"

protection to the body.

As you breathe tissues will contract in varying ways to

assist the breathing or simply in response to the breathing. Most of these tissues of the body that you

can pull and contract in synchronicity with your inhale and exhale are examples

of the qi-tissues that are involuntary-muscles attached to fascia and voluntary

muscles and bones. If we focus our

breathing exercises on these tissues we can strengthen and mobilize the

tissues. We can also affect those same

tissues by stretching the body postures along with the breathing and by

engaging those tissues via imagery and imagination.

If you know how to use reverse-breathing, and I'm assuming all qualified martial-artists and qigong practitioners know this foundational skill, you can try a simple qigong exercise for the sinuses and lungs. Tilt your head upward at about 45 degrees and do a reverse-breath inhale. One of the main functions of reverse-breathing is to allow you to engage and pull the various qigong tissues throughout the body at will, and in this case, while you're looking upward, the idea is to pull the sinus tissues downward toward the lungs (and thence toward the dantian) as you do a reverse-breath inhale. If you do enough of these lung-sinus exercises you will strengthen the tissues of the sinus and lungs. That's the bare bones of it. The illuminating point, though, is that most people that are busily teaching sinus-lung qigongs don't understand (or if they understand, they usually don't tell) the presence of these tissue mechanics in a qigong … they're usually thinking that this type of qigong has something to do with "circulating the magic qi in the sinuses". That's how our misunderstandings occur.

Not to belabor the point, but many/most of the traditional

exercises that mention the qi are in actuality referring to physical body

phenomena, but for westerners who don't understand the Chinese perspective

involving the involuntary-muscle systems and the subconscious, "qi"

is misunderstood and is accepted or taught as something you have to take on

faith. If you understand that the qi of

the body (the various skills done by the qi are also, confusingly, called

"qi") involves the various involuntary muscle-systems, you can begin learning

Chinese martial-arts, qigongs, calligraphy, and so on, in the traditional manner.

Incidentally, in this same blog is another treatment involving

the important involuntary/subconscious skill of jin. There are a number of topics like jin that would

be needed to paint an overview of the qi-systems. If there's time and if there's interest, more

topics will be posted later.

Hi Mike, thanks for the insightful article. Where can one look up the relationships between organs and body parts, such as the sinuses and lungs? I'd imagine there are other existing relationships that can be used to build exercises around. Are they common knowledge that can be referenced through acupuncture websites or books, like Peter Deadman's manuals?

ReplyDeleteHi Victor: Many of these relationships like "the qi goes in from the liver to the spleen" or "the qi goes from the lungs to the sinuses" can be found in various acupuncture books. The lungs to the sinuses is just a good basic case of this. I'm no expert in the Hindu system of "nadis", but there are a lot of these qi/prana-pathways that are enumerated in various yogic type books, too.

ReplyDeleteThank you Mike. Do you have any books or websites to recommend that lay out these nadis? Most search results simply refer to the 7 chakra model, which as you point out is just an alternate way of looking at the 3 dantian model. That doesn't shed any light on how they connect to the organs, like how the yintang relate to the sinus and lungs, or the liver to the spleen.

DeleteDo you have any experience with "mudras" or hand seals as a viable way to exercise the qi tissues? Seems like they are designed to stretch out certain pathways while locking down the rest, although it's difficult to see what the more outlandish ones are meant to accomplish.

Victor, a "dantian" is basically a joint or "nexus of movement channels" and if you think of it like that, there are more than just 3 major nexuses in the body. The 3 dantians is sort of a convenience and different people actually talk about a different 3. When I say 3 dantians I mean the crotch dantian, the main/abdominal dantian, and the chest dantian, for example. But there's a throat dantian, too.

ReplyDeleteI've seen discussions about the nadis online that get quite complex and they talk about, for example, a nadis that is involved in starting and stopping urinations, etc., but you'll need to explore that for yourself.

Hand seals come from a long way back in Hinduism and then Buddhism ... I don't know a lot about them and my feeling is that they may be more for ritual and visualization (getting back to the subconscious-mind stuff)... but that's just speculation.