Qi Ruminations

Jan 22, 2021

Qi is a

pretty old term, going back at least to the fifth century, B.C. in China. That long ago, there was not much in the way

of science to explain how the world worked, so the ancient Chinese devised

their own paradigm in a sort of "Theory of Everything": they used qi as a building block for their

hypothesis.

If you look at some of the earliest, primitive drawings in

China that show the flow of forces in the human body, you can see the

beginnings of the so-called acupuncture meridians through which qi

supposedly flows. The earliest drawings

of force paths were crude and there were a limited number of recognized

channels or force flow. The original

force-flow lines were probably delineations of the muscles and tendon connections

that support strength along different facets of the body.

The Chinese, though, recognized something that we in the

West seem to have missed, early on. The

Chinese recognized that everything about strength was not just muscle, bones,

and tendons as we lift and move things: there are supplemental involuntary

assists, like force aiming, etc., built into the body and those involuntary

supplements work with the voluntary aspects of bone and muscle. Since

the involuntary-muscle/fascia aspects of strength act to supplement the normal

voluntary actions of our strength, the actions of flow of qi tend to overlay the

normal channels of our voluntary strength.

In that sense, qi-meridians lay on top of

muscle-tendon (Sinew) channels.

So, our strength is a function of qi factors. Cheng Man Ching, in one of his books I read

early on, said that qi and strength always go together: if your qi

is strong, your strength will be strong; if you are strong, then your qi

will also be strong. Note, however, that

the qi

needs to be trained to work optimally with the body's strength. Having strong qi and controlling strong

qi

are not the same thing.

Qi has to do with factors that have to do with strength or

enhance or supplement strength. As time

passed, the Chinese mapping of the channels of strength in the body became more

sophisticated. By the time of the

drawings that were found in the Mawangdui Tombs (200+ years B.C.) the channel

theory of strength (the Jingluo theory) had reached almost the intricacy that

it has today. Bear in mind that much of

these discussions in the old days were practical matters about strength and

body exercise in rapport with the subconscious mind: traditional Chinese

medicine with its myriad examples of putatively different types of qi

didn't arise until long after the initial qi discourses.

The Strength of Man

Qi of Heaven,

Qi of Man, Qi of Earth

Where the Qi Paradigm Failed

The strength of man was originally described, in the qi-paradigm,

in terms of the Sancai, the three realms of Heaven, Man, and Earth. Man has his own strengths of qi,

as in the qi of the muscles, the bones, the tendons, and the blood, but

Man also has inputs of qi/strength from Heaven and Earth,

without whose qi the strength of Man could not exist.

From gravity we get two major strength components: the

solidity of the ground as the basis of upward forces, and the downward pull of

the weight of our body, as the basis of any downward forces we want to

apply. Both the solidity of the ground

and the weight of our bodies are functions of gravity. Gravity is thus the "Qi

of the Earth" and without the support coming from gravity, the strength of

Man could not exist.

The ancient Chinese were clever enough to notice the

auxiliary strengths from our involuntary-muscle/fascia systems, controlled by

the subconscious/Shen … so it was nothing for them to note how there is some life-important

facet to the air that we breathe, the food that we eat, our surroundings, our

genetics/heredity, and so on. The

Chinese breathing exercises may have been predated by the breathing exercises

of the Indian continent, but that is hard to discern because both places had

breathing exercises far back in historical times. The sustenance/supplement people get from

breathing and the surrounds is called the "Qi of Heaven" … and

it's the Qi of Heaven that gives us the fatal flaw to the qi-paradigm.

The problem with the "Qi of Heaven"

hypothesis is that while the inhale is used to pull inward the tissues of the

body associated with respiration (truly, those would be "qi

tissues"), the Chinese posited that at the same time we are breathing in

an invisible, unmeasurable energetic aspect of "qi". If you think about it, in those days they had

no knowledge of the actions of oxygen on the body, or blood sugar, etc., so an

etheric quantity called "qi" fit the bill admirably. In traditional terms, if I "breathe qi

in through my fingertips", I am simultaneously pulling inward along the involuntary-muscle/fascia

layers extending to my fingertips and also pulling in the etheric qi

along those same tissue channels.

Over time, because of the belief in an etheric, esoteric qi

that came into the body with an inhale, the tradition came to be that when

someone exhaled, the etheric qi settled into his mid-body at the

dantian area. In my years of experience

and observation, I cannot point to any progress in my development that could

not simply be attributed to the training of the elastic tissue and other

controls with my deliberate breathing exercises. If I "breathe in the qi

through the yintang acupuncture point between my eyes", it is a productive

training that strengthens an elastic channel from my sinus area to my stomach

and lung area. As a bonus to that one

particular "pulling in the qi", I have learned to control

the normally involuntary muscles around the sinus area and I have found out

what the Chinese said "the sinuses are connected to the qi

of the lungs". Yes, you can feel

the connection from lungs to sinuses with that exercise.

But the putative "etheric qi" is problematic. The qi-paradigm was an attempt to

explain the workings of the world long ago, before things like oxygen and blood

sugar and genetics were understood by science, so an invisible fudge-factor

like an etheric aspect of qi was just perfect. The problem is that while the discovery of

the body's built-in elastic system is a staggering addition to strength/power,

it gets overshadowed with the idea of the etheric qi and how you "sink it

to the dantian". In actuality, you

just let all qigong elastic releases end up in the dantian.

This post got started because of a question about the

difference between the "functional qi" of the body's mechanisms and

the "etheric qi".

They're part of the same general "qi", but the

developments of the body that focus on an etheric qi often take some bizarre, unsupported

turns. I remember a story about Koich

Tohei, of Aikido fame, showing some of his tangible qi/ki

demonstrations and then asking a zen monk, who supposedly meditated on his qi/ki

daily to demonstrate the same abilities.

The monk could not; his understanding of qi/ki was

unsupported by the real world. At the

risk of getting lost in the weeds, I'll stop here.

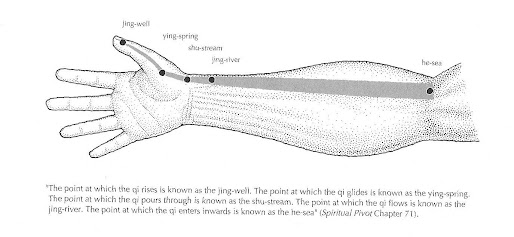

Below is a picture of one tissue channel from the thumb

inward toward the body center. Notice

the names of the way-stops and how they relate to bodies of water. That is your qi-flow.

Next are two pictures from Mantak Chia's book Bone Marrow Nei Kung. Mr. Chia is an anatomical illustrator who has been trained in various Chinese methods and he is simply illustrating here the common viewpoint of "breathing the qi in the channels at the tips of the fingers and toes". His second illustration shows that with the pull-in of the skin with the inhale, there is also the idea that you have breathed in "energy" (qi) through the skin, particularly at joints and bone protrusions.

Comments

Post a Comment